Why don’t children with CHD get enough physical activity? Studies show children with cardiac conditions typically do not engage in activities long enough to provide positive health benefits.

Because factors influencing physical activity behavior of preadolescent children are not well-known, a study was performed with 7- to 10-year-old children with moderate or complex CHD participating in a 10-week multisport program. (Blais, Lougheed, Yaraskavitch, Adamo. Longmuire, 2020)

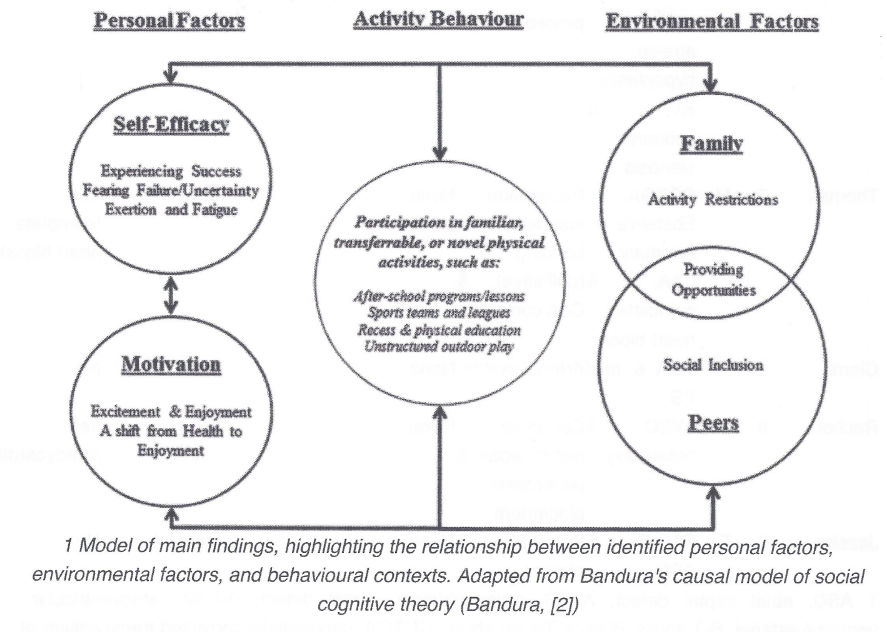

Four social factors/themes were identified during activity behaviors that included participating in familiar, transferrable or novel physical activities, such as: after-school programs/lessons, sports teams & leagues, recess & physical education, and unstructured outdoor play. Note – the results of this study emphasizing the importance of peers, family, and self-efficacy for sport are similar to prior findings among sufficiently active youth and adults with CHD, who recall the same factors contributed to their involvement in physical activities during childhood (Blais, et al., 2020).

Personal Factors:

• Motivation – Reaction shifts from health benefits to enjoyment

• Self-efficacy – Experiencing success. In contrast to Low Self-Efficacy – Fearing Failure/Uncertainty, Exertion & Fatigue

Environmental Factors – Providing Opportunities:

• Peer Influences – Social Inclusion

• Family Influences – Activity Approval or Restrictions

Motivation:

Participants didn’t view activities as being a health benefit, but saw the activities as “being fun”. This shift is important to note, children should be encouraged to continue physical activities that they had positive responses to.

When asked about if they worried about their heart during participation, the children did not say how their cardiac diagnosis impacted their participation in an activity. One child said “I don’t think I should worry about my health”. Another child said it was a difficult question but did not explain why the question was difficult. Another responded “don’t worry (about your heart) …you’re supposed to have fun! (Blais, et al., 2020).

Participating with friends is primary source of motivation among preadolescent children with CHD. This is also strongly supported among children without CHD. In active settings (gym class/recess), children with CHD showed the perception of their ability to keep up with children of the same age group was negatively impacted. The negative self-perception may impact children as young as 7 years old. The impact of social influence is supported by knowledge that children as young as 5 years old begin to compare the development of their own skills to those of their peers (Blais, et al., 2020).

Self-Efficacy:

Each person uses social media for different reasons. The most negative impact on romantic relationships is for the people that show tendencies of attachment anxiety – high fears of rejection endorsement of relationship insecurities, and maladaptive interpersonal tendencies. Persons with attachment anxiety might excessively monitor their partner’s online activity which can lead to romantic jealousy. Jealousy can also be triggered from the perception of closeness from a partner’s online interactions with parties perceived to be “rivals.” This can have negative consequences, leading to romantic dissatisfaction, conflict, cheating or even divorce. People with attachment anxiety tend to have a need to post about their romantic relationships. They have a strong desire to make sure their relationships are visibly known (Leung & MacDonald, 2022).

Low Self-Efficacy:

If the child felt unable to participate, they expressed feelings of frustration, nervousness and fatigue due to feeling like they were “not very good” with a specific skill. In some cases, the child would not even attempt to participate saying “I’m not good enough” or “I can’t do that” due to the perception of failure.

Many children with CHD, have neurodevelopmental delays and lower physical capabilities which can hinder the child’s ability to successfully perform sport-related skills. Participants exhibited both high and low levels of self-efficacy depending on influences of prior experiences with a particular sport. If prior experience resulted in feelings of frustration or failure, the child will be reluctant to try again. But, if a child tried a new sport and felt that they could do it, positive self-efficacy develops and the child is more likely to continue the activity.

Exertion and Fatique:

all children expressed feeling exertion/fatigue during the program, especially during running activities. These moments of fatigue did not impact the child’s enjoyment or participation in the program. Note – it a possible that frequent moments of exertion could subtly impacted their self-efficacy for participating in programs with cardiorespiratory fitness (i.e.: running in soccer) (Blais, et al., 2020).

Peer and Family Influences:

“I really like playing games together!” Playing with others gave the children a reason to participate in activities. For example, one child said that she would like to try hockey because their neighbors had a hockey net that she watched them play. Note – this could be dependent on the child’s self-efficacy for the particular activity. They might watch someone play and think that they could play successfully or they might assume they wouldn’t be very good at that particular activity.

Peer influences also introduces feelings of social inclusion. The child might want to try a new activity because a friend is an active participant in a program. In many cases, trying a new activity opens the door to the child learning a new skill and meeting new friends.

Family Influences:

Family influences have a great impact on the child. Families that were consistently active and encouraged their child to try new programs were seen as positive role-models.

Parents:

Parents play an essential role in supporting an active lifestyle for their children. Parents often introduce new opportunities to their children. In some cases, children with CHD often have delayed motor development and can be smaller/lighter compared to their peers. This might result in the parents perceiving the child’s physical competence is low, which could lead to a reluctance to support their child in activities. This reduced parental support is referred to a bubble-wrapping. In this study, the willingness of the parents to allow their child to participate in the program indicates the parents support their child’s participation if the activity/sported is deemed appropriate for their child (Blais, et al., 2020).

In some situations, parents were hesitant to introduce new activities. They were either unsure about what activities were safe and appropriate for child or they didn’t know when necessary medical restrictions were required. This is challenging for parents in their efforts to provide safe and fun physical activities. Depending on the medical restrictions required and with doctor approval, the child might benefit from participating in an activity program designed for children with special needs.

Community-based and/or multi-sport programs might also be a wonderful tool for children from a young age that they can maintain through adolescence. These programs provide a variety of activities that the child can learn and enjoy with their friends. It also provides the opportunity for the child to discover what activity they really like, promoting long-term participation in that particular activity. Keep in mind, the activity should always be aligned with the individual needs and skill level of the child to encourage participation and develop a desire to continue to play and connect with their family and peers. It is not known how children with more complex diagnoses will respond to these activities since they often have motor skill delays and decreased aerobic fitness (Blais, et al., 2020).

Enjoyment is also a strong factor of the physical activities of the children, in addition to the four social themes. When children expressed a positive emotion (I really had a good time!), they are more likely to continue participating in the program/activity.

This study shows that children with CHD are aware of the health benefits of an active lifestyle, an important external motivator. However, during the study in the community-based program, the shift in perception emphasized enjoyment over health benefits. Enjoyment of any physical activity is known to have a positive effect and contributes to the continuance of an active lifestyle in childhood.

Clinicians – should address differences in physical activities and communicate clearly to patients and their families about how activities may or may not impact cardiac health.

Conclusion

The results of this study show how the interaction between personal and environmental factors contribute to the overall physical activity among preadolescent children living with CHD. This group of children greatly benefit from programs designed to encourage participation with friends and engage in new activities to develop skills. In many areas, community-based programs focused on physical activities (multi-sports) may be available. These programs are great social, physical activities that can provide meaningful and positive experiences for the child.

Clinicians should be aware of the impact of social influence when providing physical activity counseling to parents and younger patients. The child might have the inability to have similar skill levels which may discourage children with CHD from participating in regular activities with friends. The findings emphasize the need to intervene before adolescence, while highlighting the potential effectiveness of introducing a variety of physical activities to this unique group (Blais, et al., 2020).

Physical activity is important for all children in the development of both physical and psychosocial needs. Children who are consistently active are more likely to benefit from healthy outcomes when compared to children with a sedentary lifestyle. Research has been done that shows the health burden associated with sedentary lifestyles (limited activity) is a leading risk factor for morbidity worldwide.

While physical activities contribute to improving the overall quality of life, they also play an important role in preventing the risk of developing comorbidities in children with chronic disease. Children with CHD have a greater risk of developing cardiovascular and metabolic diseases, show increased signs of depression and anxiety, which can be mitigated with physical activity (Blais, et al., 2020).

Sadly, despite various opportunities for physical activity, children with chronic disease are not meeting recommendations to support healthy outcomes.

This visual chart was included in the study. This is very helpful in showing how the different factors interact.

Heart and Mind Counseling specializes in providing services to all patients and their families dealing with chronic diseases including congenital heart disease. Dr. Smorra is a licensed Clinical Social Worker in the states of Alabama, Colorado, Florida, Georgia, Kansas, Massachusetts, Michigan, New Jersey, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Iowa, Texas, and Wisconsin. She specializes in psychosocial issues for families and clients affected by Congenital Heart Disease and has written her doctoral dissertation on the subject.

For more about Dr. Smorra and her research please visit https://www.linkedin.com/in/dr-corinne-smorra-dsw-msw-lcsw-439a9ba/ or www.heartandmindcounseling.com.